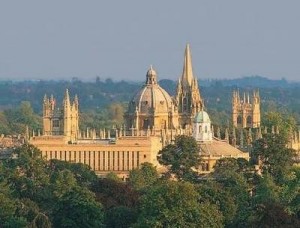

Fredagskommentaren i dag er en lesefrukt fra ukens arbeid her i Oxford. Det er en tekst fra en av byens virkelig store tenkere, John Henry Newman (1801-1890). Om boken teksten er hentet fra skriver Frank Turner : No work in the English language has had more influence on the public ideals of higher education. Og som ikke dette var nok, selveste Jaroslav Pelikan sier følgende om den: This is the most important treaties on the idea of the university ever written in any language. Det Newman gjør i denne teksten er å gi et komprimert uttrykk for kjernen i pedagogisk tenkning fra antikken av. Han beskriver hva som er ledestjernen i all karakterutvikling innen høyere utdanning, forankret i idealet knyttet til det som kalles for liberal education eller klassisk dannelse.

Teksten er altså hentet fra Newmans bok “The Idea of a University” og jeg overlater til leseren selv å nyte teksten uten videre kommentarer fra min side. Den kan gjerne også læres «by heart».

«A University training is the great ordinary means to a great but ordinary end; it aims at raising the intellectual tone of society, at cultivating the public mind, at purifying the national taste, at supplying true principles to popular enthusiasm and fixed aims to popular aspiration, at giving enlargement and sobriety to the ideas of the age, at facilitating the exercise of political power, and refining the intercourse of private life. It is the education which gives a man a clear conscious view of his own opinions and judgments, a truth in developing them, an eloquence in expressing them, and a force in urging them. It teach him to see things as they are, to go right to the point, to disentangle a skein of thought, to detect what is sophistical, and to discard what is irrelevant.

It prepares him to fill any post with credit, and to master any subject with facility. It shows him how to accommodate himself to others, how to throw himself into their state of mind, how to bring before them his own, how to influence them, how to come to an understanding with them, how to bear with them. He is at home in every society, he has a common ground with every class; he knows when to speak and when to be silent; he is able to converse, he is able to listen; he can ask a question pertinently, and gain a lesson seasonably, when he has nothing to impart himself; he is ever ready, yet never in the way; he is a pleasant companion, and a comrade you can depend upon; he knows when to be serious and when to trifle, and he has a sure tact which enables him to trifle with gracefulness and be serious with effect…»

It prepares him to fill any post with credit, and to master any subject with facility. It shows him how to accommodate himself to others, how to throw himself into their state of mind, how to bring before them his own, how to influence them, how to come to an understanding with them, how to bear with them. He is at home in every society, he has a common ground with every class; he knows when to speak and when to be silent; he is able to converse, he is able to listen; he can ask a question pertinently, and gain a lesson seasonably, when he has nothing to impart himself; he is ever ready, yet never in the way; he is a pleasant companion, and a comrade you can depend upon; he knows when to be serious and when to trifle, and he has a sure tact which enables him to trifle with gracefulness and be serious with effect…»